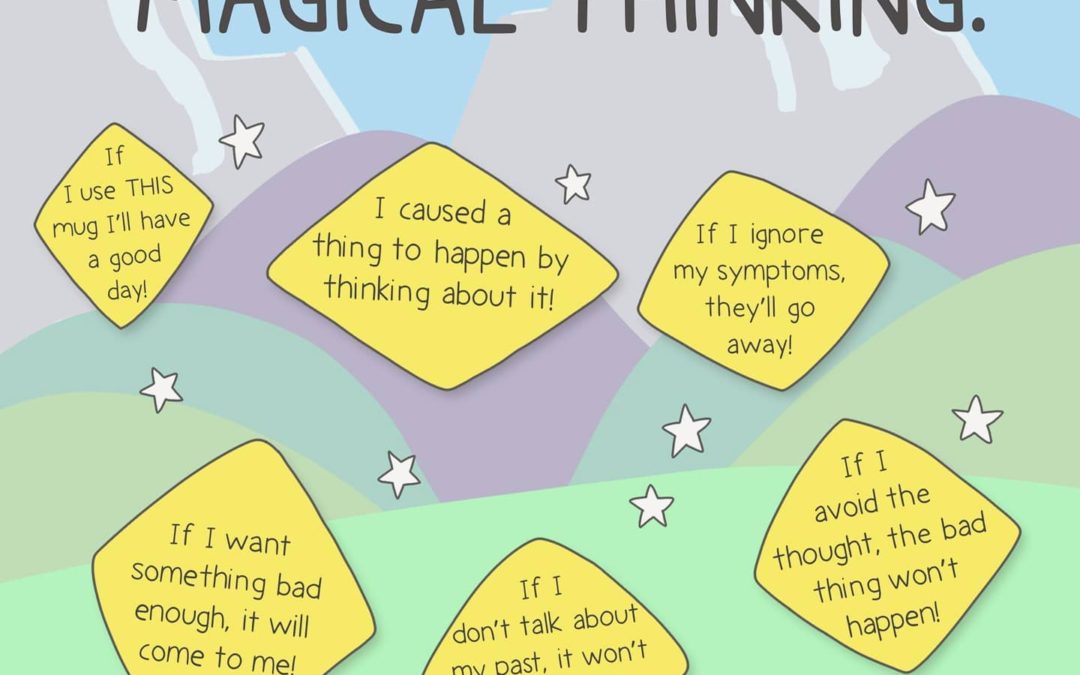

Magical thinking: Magical thinking, or superstitious thinking, is the belief that unrelated events are causally connected despite the absence of any plausible causal link between them, particularly as a result of supernatural effects.

For every magical belief, an aspect of embodiment goes unfulfilled.

This is because embodiment also depends upon abiding what is most likely true.

What’s so tough about abiding what is most likely true?

The difficulty is abiding the part of reality that makes us feel badly, which feelings are, ostensibly, what magical beliefs and a lack of willingness to dismantle false beliefs, help to stave off.

Because reality is difficult—whether it’s a a broken heart, a challenging health condition, a fear of death or loss of meaning, or the deteriorating condition of the world—most magical beliefs falsely satisfy feeling better about any of these conditions without being honest and accurate about them.

On the other hand, reckoning with any of these realities brings us down . . . into our bodies, into our feelings and emotions, into feeling less rosy than we’d prefer—and on a good day, into acting to help heal the condition.

But we can’t better the condition if we don’t acknowledge it accurately at face value. This is why medical diagnoses have to be accurate. So, abiding what is most likely true not only puts us immediately in touch with our human vulnerability and shadow, but also aligns us with being able to actually improve the situation.

Our human vulnerability and shadow, devoid of magical beliefs to keep us “positive” and disengaged, are the heart of embodiment, because the take us down, not up. To embody, we must go down into our bodies. As Rumi says, “Love flows down.”

Yes, we must also go up in joy and pleasure, but this axis is over-exercised in our western world and too often used to avoid the difficult. Ultimately, toxic positivity is a privilege to remain in denial about difficult reality, which disproportionately and negatively affects the less privileged . . . which is, de facto, a violence.

Frankly acknowledging and feeling the effects of disease, human injustice, environmental abuse, disregard for others, needless violence, lack of accountability, and the climate crisis . . . these all bring us down into our bodies. When we choose to float through life without acknowledging and feeling (embodying) these—opting, often unconsciously, for magical beliefs instead—we deny ourselves fullness and compassion and the healing of ourselves and our world.

One can fritter along this way for some time enjoying the privilege of a superficial life, but usually not amount to ever landing deeply on earth, in one’s body, and contributing something rich and deeply helpful to help the greater good (though one, of course, will imagine they are).

If one wants a more potent, deeper, richer, more meaningful and compassionate life, the rub—the pivot—is to make friends with difficult feelings and one’s shadow, for it’s the avoidance of these difficulties that perpetuates magical beliefs and denial.

When one can tolerate feeling badly, and then learn to leverage these feelings into more soulfulness, then one can exercise one’s critical thinking mind to dismantle one’s magical beliefs. But until one can be comfortable enough with fear, grief, anxiety, anger, and remorse, one will not be able to stomach using one’s mind to deconstruct false beliefs about oneself, others, and the world—because apprehending what is more likely true seems too painful. This is why arguing with people who are afraid to feel badly is futile. This knee-jerk reaction, ironically, is also a false belief that getting close to the pain will destroy or kill oneself, because emotional and physical pain are processed by the brain along the same neurocircuitry. Ironically, the opposite is truer: getting close to pain offers the chance for renewal via a figurative, not literal, death . . . and eventual rebirth.

Thus, grokking the circular reality, the promise of death and rebirth, versus mere linear pain and suffering can unlock a willingness to embrace the darker side of life, and thereby free one to give up false beliefs, conspiracy theories, and lies . . . and actually be helpful to oneself and others, instead of perpetuating the same to others who need a quick, magical belief fix.

So, when we can befriend our pain, we can think more accurately and robustly and let go of false beliefs, allowing us to more fully embody and join the heart of the world for its healing, which creates more equality and joy.

When we are able to give up false beliefs, we create an injunction for ourselves to find real and sustainable joy, meaning, and fulfillment in our own bodies, where we must mine our own resources along with the embodied, non-magical support of others.

Thus the practice of giving up false beliefs—which often necessitates the willingness to challenge our beliefs and to feel badly in the short-term—becomes a path for embodied spirituality, or simply being more fully, authentically, and compassionately human.